Archaeological Illustration at Pyla-Vigla

Larnaka, Cyprus (summer 2024)

about the dig

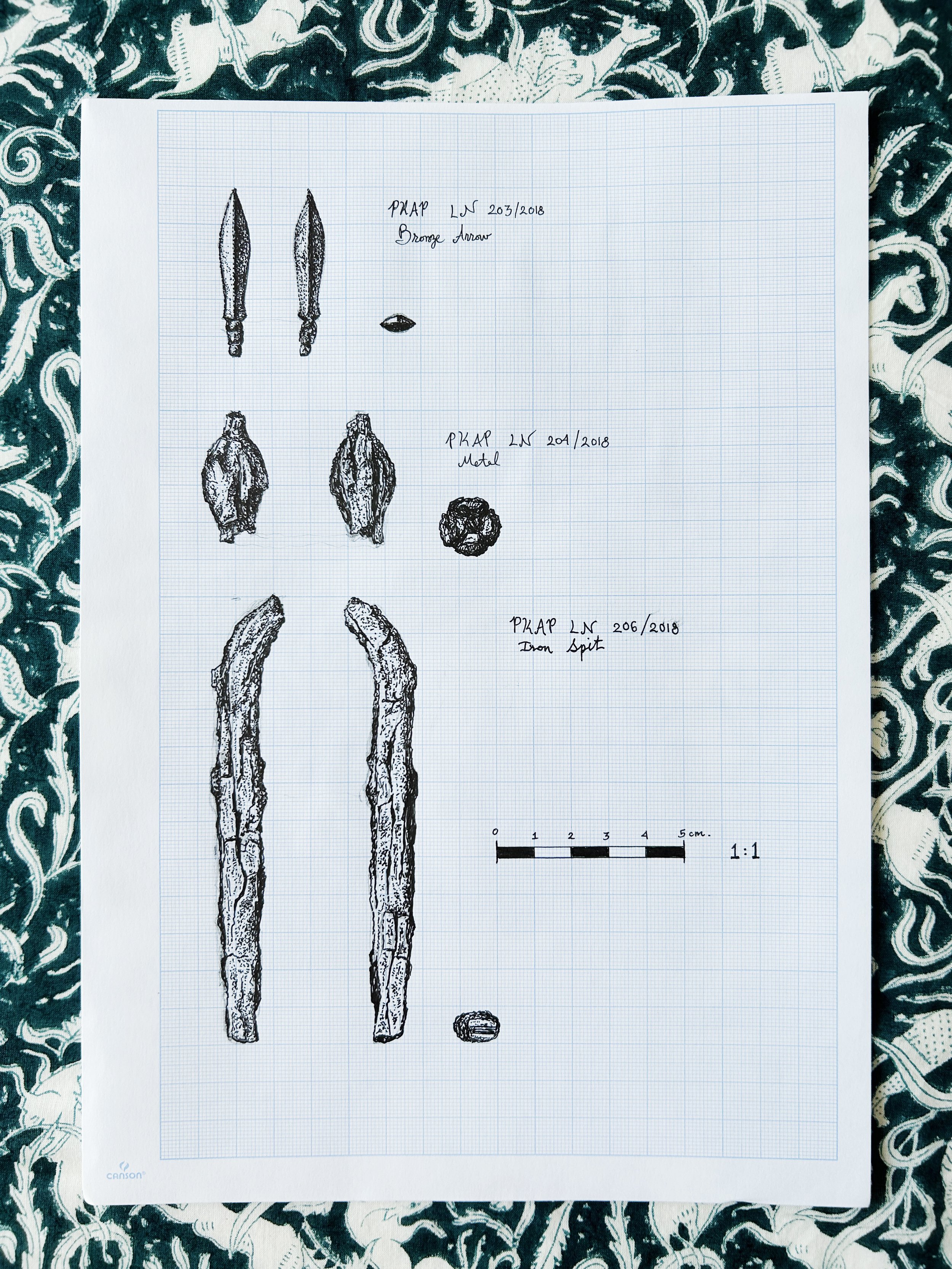

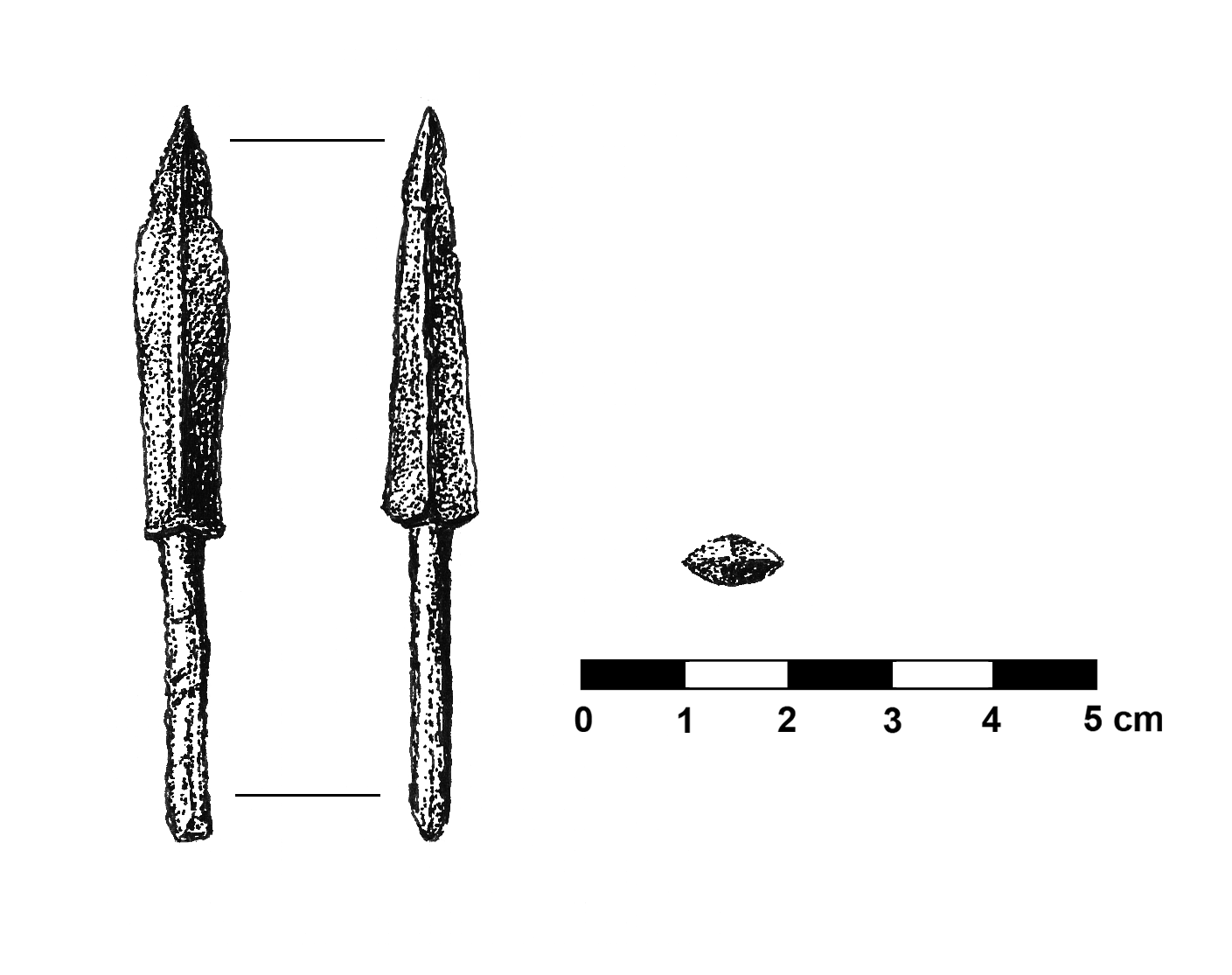

On the western side of Larnaka Bay in Cyprus, overlooking the Mediterranean, lies an imposing plateau known as Vigla. This fortified settlement, occupied briefly during the years when Alexander the Great controlled the area, has yielded a rich array of finds, including metal projectiles, ceramics, carved figurines, and molds for casting and producing weaponry.

During the summer of 2024, I traveled to Cyprus, offering my artistic skills to this excavation, which is being studied under the auspices of the Pyla-Koutsopetria Archaeological Project (PKAP). This site is unique as the only Hellenistic fortification discovered to date, yielding numerous discoveries that illuminate the region's history.

my role as illustrator

I spent most of my time working on drawings in the Larnaka Archaeological Museum, where all of the PKAP finds are safely kept in labeled boxes. Holding each artifact in my gloved hand, I would rotate it under the lamp, examining subtle details, like scratches and carved patterns.

Using a Staedtler pen, I created my drawings with a stippling technique, slowly adding dots to build up texture and shadow. This method allowed me to capture details that might otherwise go unnoticed, ensuring that each artifact was represented as accurately as possible. Every drawing was a focused effort to faithfully document these ancient objects.

How I Got Involved

I learned about PKAP during my final semester of graduate school at Boston University. While enrolled in the MFA Painting program, my work increasingly incorporated diagrams and imagery from books about archaeological digs, leading me to audit a class taught by Professor Andrea Berlin called Archaeological Studies in Ceramics.

One week, she invited a professional archaeological illustrator, Cathy Alexander, to demonstrate how to use calipers and millimeter-grid paper to create accurate 1:1 drawings of ceramic vessels and figurines. Given my strong interest in drawing artifacts and using line drawings to describe the surfaces and contours of objects, Professor Berlin connected me with the co-directors of PKAP, including Professor Brandon Olson (a former student of hers). With generous support from the project and a Dig Fellowship from the Biblical Archaeological Society, I traveled to Cyprus and participated in my first-ever archaeological dig.

Working at the larnaka Museum

Although PKAP began in 2003, the project had never involved an artist, resulting in a backlog of special finds and metal objects to be illustrated. The museum staff at the Larnaka Archaeological Museum provided invaluable support, retrieving trays of artifacts from previous excavation years based on a list provided by the PKAP co-directors. I would then identify which items needed to be drawn.

I began each drawing by carefully measuring the artifact’s dimensions using digital calipers. Then, on millimeter-grid paper, I used a pencil to sketch the outlines of the object at a 1:1 scale. I positioned a lamp to shine from the upper left—a standard in archaeological illustration—to highlight the texture and contours. Typically, I illustrated each object from several significant angles, including a frontal view, a side view, and a section.

Other archaeological illustrators I’ve met have emphasized that these technical drawings should always be done from life, never from photos. During my time at the museum, I appreciated being able to hold the objects and rotate them, understanding how they were constructed and carved. This hands-on approach allowed me to better capture and emphasize their form in my drawings.

why not just take photographs?

In archaeology, objects are routinely photographed for inventory purposes, yet illustrations are preferred in publications for their greater clarity and ability to reveal texture and details often lost in a photograph. Drawings are carefully measured, usually created at 1:1 scale with the artifact directly in front of the illustrator, ensuring more accurate proportions than a photograph, where the lens curvature can distort contours. For some objects I illustrated, the faintly-carved imagery was only visible under extreme raking light, making it invisible in a regular photograph.

Illustrators can choose to emphasize particular features of an artifact that are important for analysis, such as decorative patterns, manufacturing techniques, or damage that indicates usage.

Drawings also provide a standardized way of depicting artifacts, which can be easily compared across different sites and publications. This helps in identifying similarities, differences, and broader cultural patterns.

the bread stamp

One of my favorite objects to illustrate was a small limestone ‘bread stamp’ with a decorative floral motif carved into its surface, used to make designs on fresh loaves of bread, perhaps for special ritual purposes.

At left is the PKAP photograph showing the original find-spot of the ‘bread stamp’ amongst ceramic sherds, before cleaning. The limestone surface doesn’t show any staining or smoky marks from being in an oven, and archaeologists aren’t quite sure how these ‘bread stamps’ were utilized in antiquity.

Happily, PKAP gave me permission to make a 3D scan of this object, and I’ve since created a to-scale 3D print. Below are some cookies I made using the 3D-printed mold to imprint the ancient pattern and bring the design to life again.

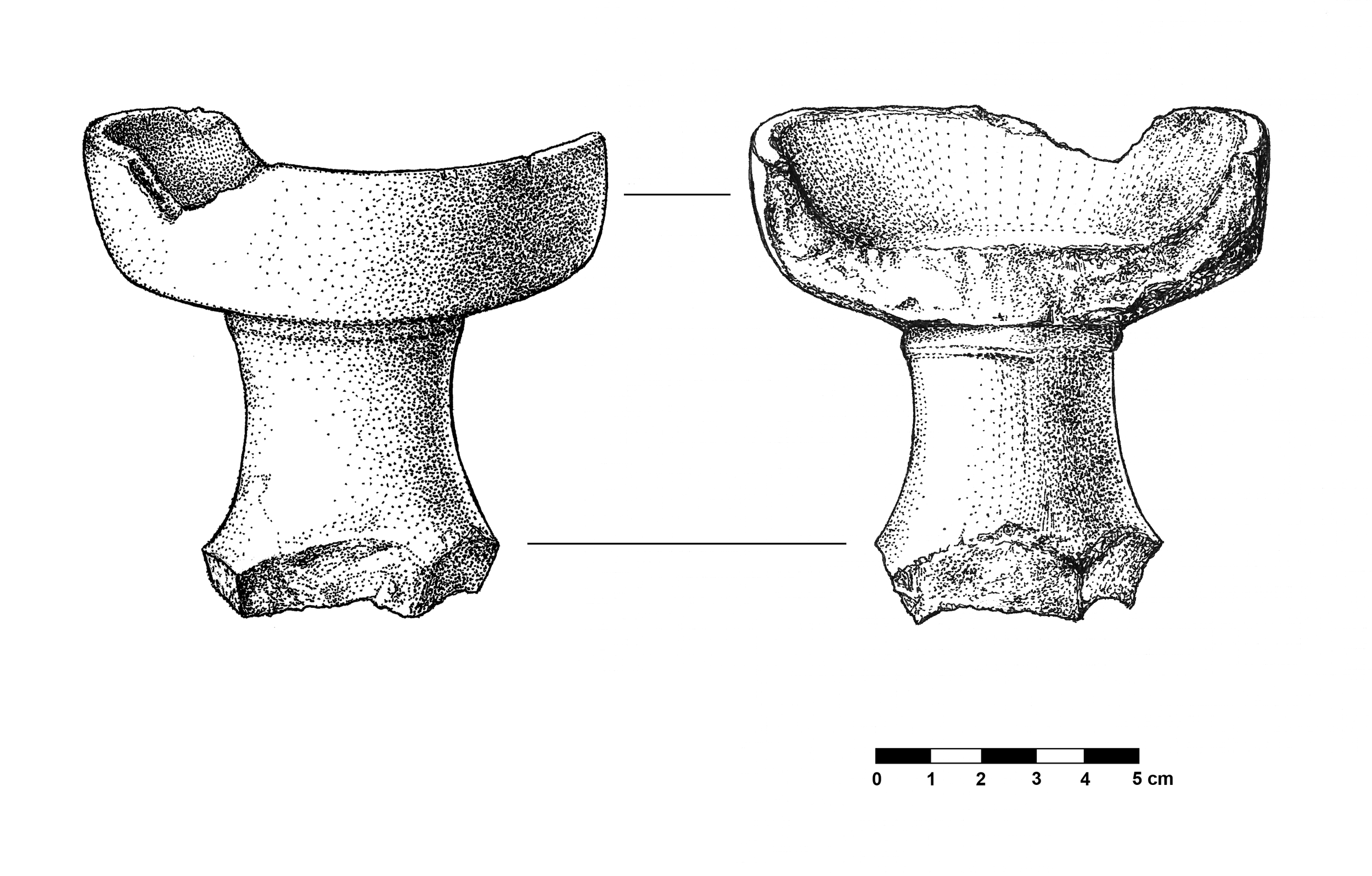

the eastern figurine

Another object I particularly enjoyed drawing was a fragmentary torso of a man, dubbed the ‘Eastern Figurine’ by PKAP due to the figure’s long, textured beard, reminiscent of styles popular in the Ancient Near East. The figure was carved from the warm-toned, finely-grained limestone commonly used for carving in Cyprus.

Reconstructions

One of the exciting challenges of the project involved creating reconstruction drawings of the Hellenistic fortifications. After visiting the dig site, where co-directors highlighted certain topographical features, I used pen, brush, and India ink to create renderings of the site as it might have looked around 300 BCE, with mud-brick walls atop fieldstone foundations.

Newest finds at Vigla

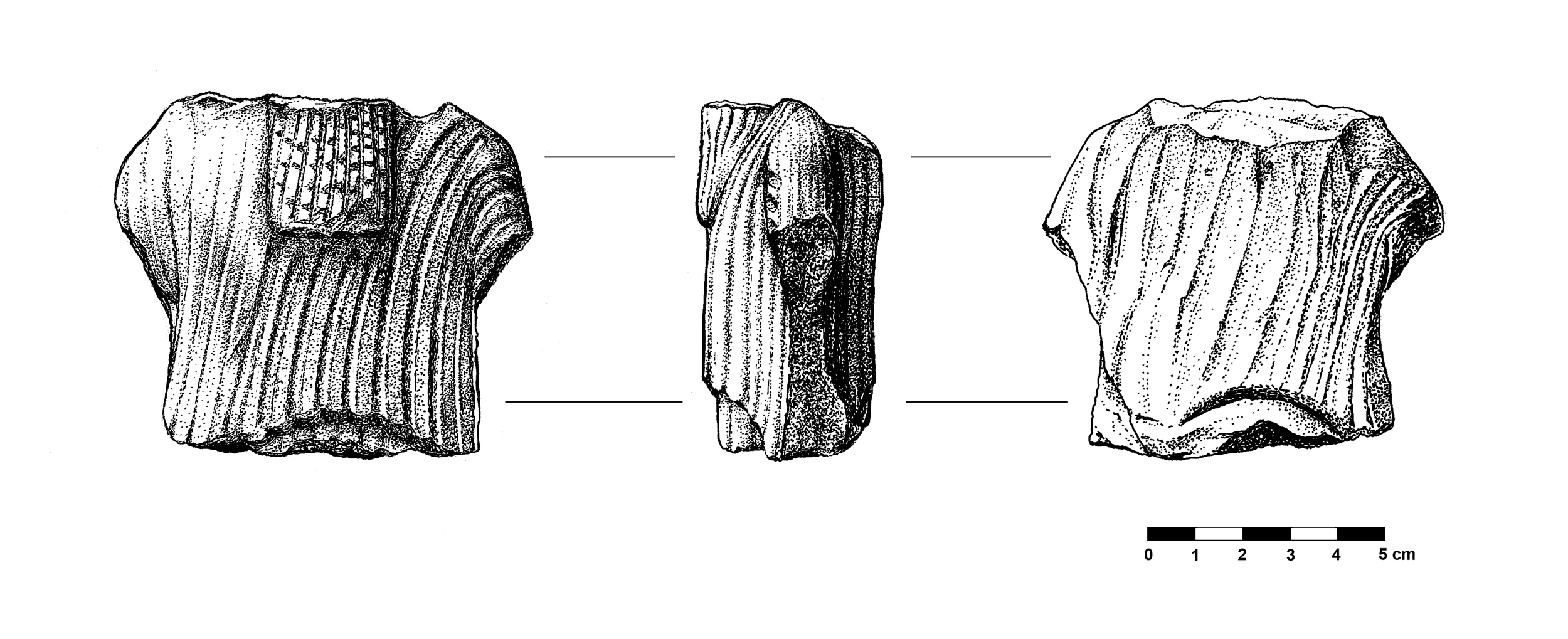

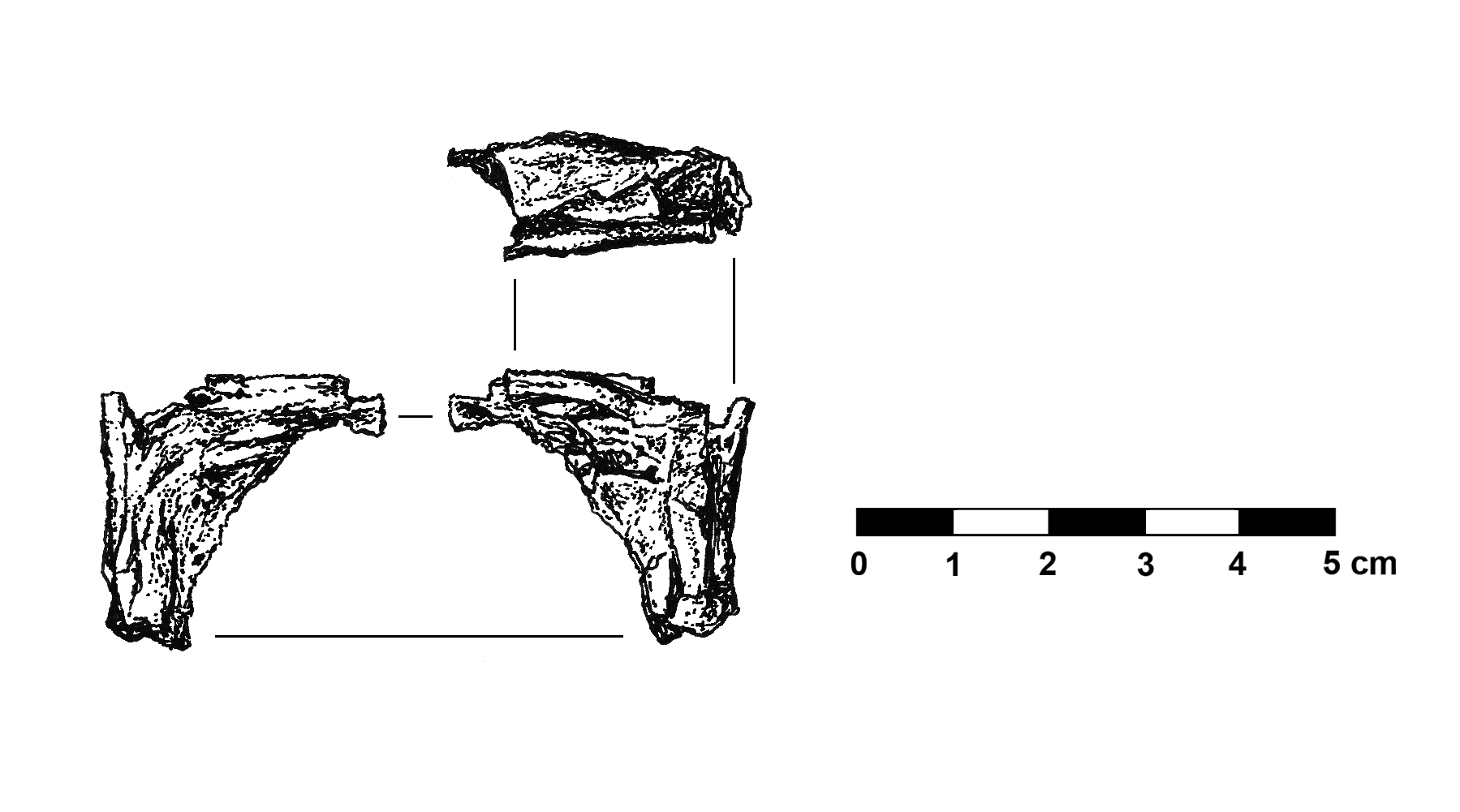

A recent and exciting find at Vigla was a mold, carved from limestone, used to cast blades for knives or daggers. Several holes were drilled into the stone to fasten it to another surface.

According to the co-directors, this find dramatically changed archaeologists’ understanding of the site, revealing that it was not just a military outpost but also a major production center for weaponry on Cyprus during the Hellenstic era.

connection to my artistic practice

Holding objects that were crafted over 2,000 years ago has deeply influenced the way I think about making art. These objects, created by anonymous artisans, carry an immediacy and intimacy that I aspire to in my own work. Their surfaces—worn, scratched, or still bearing faint tool marks—tell stories about the hands that shaped them, the lives they passed through, and the environments they endured. I’ve begun to see my paintings as fragments of an imagined archaeology, echoing these qualities of transformation and survival over time.

As I worked on drawings in the Larnaka Museum, tracing the contours of a limestone figurine or mapping the intricate details of a bread stamp, I felt a quiet connection to the ancient maker. The care and precision I put into each drawing reflected my personal way of honoring their craftsmanship.

Many thanks to PKAP, the Biblical Archaeology Society, Cathy Alexander, and Professor Andrea Berlin for their essential support, which allowed me to join the Summer 2024 Dig Season at Pyla-Vigla.